Credit Suisse Group is a global financial services company with a history of over 160 years and a presence in more than 50 countries. CS is a global wealth manager, investment bank and financial services firm founded and based in Switzerland, growing to be large investment bank and wealth manager for the ultra-rich.

What happened last week?

On

Tuesday, 14 March, Credit Suisse said in its 2022 annual report the bank has

identified “material weaknesses” in

internal controls over financial reporting and not yet stemmed customer

outflows.

The

reporting of material weaknesses came even as Credit Suisse was seeking to recover from a string

of scandals that have undermined the confidence of investors and its clients.

Customer outflows in the fourth quarter rose to more than 110 billion Swiss

francs ($120 billion).

A

week before this revelation Harris Group, one of CS’s major and long-standing shareholders,

sold all its stake in CS, creating nervousness amongst investors.

Harris Group's CIO for International equities, David Herro, said this in a Financial Times interview:

“It has been a

measurable drag on our performance... We meet every company we own, but you

spend a lot more time with your problem children. Credit Suisse has been a drain

of time and value for years.”

According to CS’s

filings, depositor outflows have been much more severe than anyone may have

realised. CS's most recent annual report shows how the bank lost a staggering

$120 billion of client funds in just the last quarter of 2022.

Reuters reported

that Swiss regulator FINMA is investigating comments made by Lehmann at a

December 1st conference, in which he claimed that outflows had "completely

flattened out" and "partially reversed." This contradicted with CS’s regulatory

filings, which showed a deluge of outflows even as the Chairman made those

statements.

Bank run on CS seemed to be a top concern for Harris Group. It is reported that CS is now offering

aggressively higher deposit rates to attract new funds from wealthy clients to

reverse the tide. Obviously, this comes at a higher cost denting its

profitability and threatening the viability of its business model going forward.

Meanwhile the strategic investor, Saudi National Bank (SNB), expressed that it will not be able to provide further capital support due to regulatory constraints.

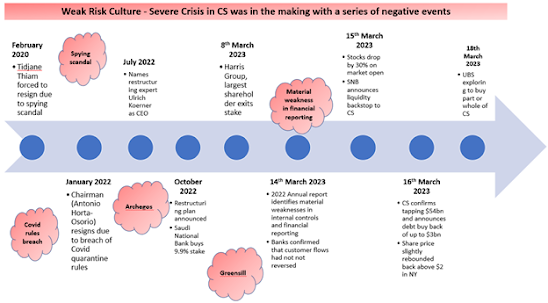

Over the past couple of years, CS's stock price has continued to slide due to its brush with one scandal after another.

But what ails Credit Suisse?

At the heart of CS’s

woes is its “POOR RISK CULTURE” and this emanates right from

the top. The risk ethos was lamentable judging by CS's CEO and Chairman's conduct. CS’s CEO (Tidjan Thiam) was

forced to resign following a corporate surveillance scandal in March 2020 and

its Chairman (Antononio Horta-Osario) was forced to resign in January 2022 following

breach of Covid 19 protocol on several occasions.

CS has been stumbling from one scandal to another that

illustrates its weak risk culture, poor risk management and an inadequate

compliance framework.

Listed below are CS’s major scandals which reflect its poor risk culture and weak risk management and a monumental failure of all the three lines of defences.

The timeline of its repeated risk management failures demonstrates its poor Risk ethos and lackadaisical approach to Risk management. The following is a brief summary of their blunders:

1.

Return of stashed

money of Ferdinand Marcos – In 1995, CS was among the Swiss

banks ordered to return nearly half a billion dollars stored in the accounts of

Philippines ex- President Ferdinand Marcos, funds which the Philippines said

was “plundered from the national treasury”, reported the AP at that

time. It was later revealed that

Credit Suisse opened accounts for the dictator and his wife under the names

“William Saunders” and “Jane Ryan”, which helped to “shield their funds from

scrutiny”, said The Guardian.

2. Sanctions breaches – In 2009, CS was fined $536m for violating US sanctions against Iran and several other countries, including Libya, Sudan, Myanmar and Cuba, between 1995 and 2007.

3. Corporate Surveillance Scandal - CS’s former chief executive Tidjane Thiam was forced to leave the bank in March 2020 after an investigation found that it had spied on two of its employees. The bank hired private detectives to follow Iqbal Khan, its former head of wealth management who was leaving to join its arch-rival UBS, and on Peter Goerke, its former head of human resources. The private investigator hired for surveillance of the head of wealth management committed suicide.

CS repeatedly played down the spying allegations but in October last year the Swiss Financial market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) said that the bank had planned spying operations on seven occasions between 2016 and 2019; and carried out most of them.

An independent

report found that its losses were the result of “a fundamental failure of risk management

and control at its investment bank, and its prime brokerage division.

5.

Greensill Capital

collapse - The bank was forced to suspend $10bn of investor

funds in March 2021 when the British supply-chain lender Greensill

Capital collapsed.

Credit Suisse had

“sold billions of dollars of Greensill’s debt to investors, assuring them in

marketing material that the high-yield notes were low risk because the

underlying credit exposure was fully insured”, said Reuters. Several

investors have sued the bank over the Greensill-linked funds, with the bank

still in the process of trying to claw back money for clients.

The bank said in September last year that it had

returned about $6.3bn to investors, but has warned it may not be able to recover

another $2.3bn of losses.

6.

Tuna Bond Scandal - CS

was fined nearly $400m by global regulators in October 2021 after

pleading guilty in a long-running scandal that pushed Mozambique into a

financial crisis. The Tuna bonds scandal

resulted from Loans arranged by CS between 2012 and 2016 for the

Republic of Mozambique to the tune of $1.3bn.

This was aimed at government-sponsored investment schemes including

maritime security projects and a state tuna fishery.

But a portion of the

funds were unaccounted, and one of Republic of Mozambique’s contractors was

later found to have covertly arranged kickbacks worth at least $137m, including

$50m for bankers at Credit Suisse meant to secure more favourable deals on the

loans, regulators found. The international scam resulted in the

International Monetary Fund (IMF) to suspend its assistance to Mozambique,

ultimately causing a financial crisis in the country.

7.

Chairman breaches

Covid-19 rules - Antonio Horta-Osorio resigned as Credit Suisse

chairman on 17 January 2022 after repeated breaches of Covid-19

quarantine rules, less than a year after taking up the role.

An investigation by

the bank’s board found that Horta-Osorio, had broken quarantine rules several

times, “including on a trip to London last year to watch the Wimbledon tennis

finals”, reported the Financial Times.

Credit Suisse immediately appointed board member

Axel Lehmann as its Chairman, who had been “at the helm for only five weeks”

before the massive data leak, said The Guardian.

8.

Data leak – February

2022 - CS has been known to have more than 18,000 accounts for

an extensive list of clients involved in torture, drug trafficking, human

rights abuses and other serious crimes. The

accounts hold more than 100bn Swiss francs, reported The Guardian

based on a data leak. The leaks point to “widespread failures of due diligence

by Credit Suisse, despite repeated pledges over decades to weed out dubious

clients and illicit funds”, said the paper, which was part of a consortium of

48 media outlets given exclusive access to the data.

CS either opened or maintained bank accounts for an range

of high-risk clients including “a human trafficker in the Philippines, a Hong

Kong stock exchange executive who looted Venezuela’s state oil company, as well

as corrupt politicians from Egypt to Ukraine”, said The Guardian. The information was initially leaked to German

newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung by an anonymous whistleblower, who said Swiss

banking laws were “immoral”.

CS’s attempted to bolster its reputation by wooing new institutional anchor investor and strengthen its capital position.

In October 2021, Saudi National Bank made an equity

investment of $1.5bn for a 9.9% stake in CS. The capital ratios appear strong, though

the haemorrhaging of its client deposits is its principal cause for worry. Despite continuing to

lose its customer deposits, it maintained satisfactory liquidity ratios, and it

carried low interest rate risk.

Is CS's business model broken?

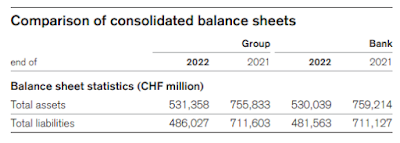

The net loss attributable to shareholders for 2022

was CHF 7.3 billion, compared to a net loss attributable to shareholders

of CHF 1.7 billion in 2021. The net

loss attributable to shareholders for 2022 included an impairment of deferred

tax assets related to comprehensive strategic review of CHF 3.7 billion

taken in the third quarter of the year.

All the divisions, except for the Swiss Bank, reflect poor profitability bringing into question the viability of its business model.

The Balance Sheet shows a decline of CHF 225bn in its total liabilities, confirming a massive decline in its customer deposits of CHF 155bn in 2022.

Strategic Review - Restructuring Plan

Ulrich Korner’s

three-year

recovery plan involves 9,000 job cuts, dismantling the investment bank (Credit

Suisse First Boston) assembled over five decades and returning Credit

Suisse to its origins as banker to the world’s ultra-wealthy. That entails spinning

off CSFB, an American investment bank it acquired in 1990 with a view to

listing it in 2025, and selling parts of its securitised products group unit to

Apollo Global Management, which it has confirmed that in an advanced stage of

execution.

The

CEO is seeking to protect the best-performing investment bank parts, such as

advising on mergers and acquisitions, while pivoting the parent company further

toward wealth management.

However, all of this may not come to pass!

On

March 9, the US Securities and Exchange Commission queried the bank’s annual

report, forcing it to delay its publication. On Tuesday, 14

March, Credit Suisse said in its 2022 annual report the bank has

identified material weaknesses in internal controls over financial

reporting and not yet stemmed customer outflows. The bank also said customer outflows had stabilised

but “had not yet reversed”.

Meanwhile,

panic in the US market spread following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank,

Signature Bank and Silvergate Bank. The contagion

spread to other regional US Banks as stocks of these banks lost between 35% to

80%, and there was significant deposit flight from these regional banks to

larger US Banks.

Amid

all this turmoil, CS’s shares drop by as much as 30% after its

largest shareholder Saudi National Bank said it could not provide more support

because of regulatory constraints. Several Banks started to cut their

counterparty limits to CS. The

cost of insuring CS’s bonds against default for one year surged to 836bps, a

level not seen for major international banks since the financial crisis of

2008.

This prompted Credit Suisse to ask the Swiss central bank for a public statement of support. Swiss National Bank issued a statement that it was prepared to provide liquidity if needed. Credit Suisse secured a $54 billion lifeline from the Swiss central bank to shore up liquidity, the first major global bank to get emergency funding since the 2008 financial crisis.

The Swiss authorities provide assurances that Credit Suisse has met “the capital and liquidity requirements imposed on systemically important banks”.

CS

has substantial liquid assets to call upon and access to central bank lending

facilities, and is less sensitive than many rivals to sharp moves in interest

rates.

A disorderly failure of CS would cause a crisis similar to that experienced in 2008, a situation all Central Bankers wish to avoid. Swiss National Bank will be at the forefront to prevent such a crisis.

There is a growing speculation that UBS, its rival, in advanced stages to acquire part or whole of Credit Suisse.

A 160+ years of CS’s Banking history is likely to come to an end.